Xin Chào

This initiative was created from the need to understand how a Czech-Vietnamese identity is influenced and shaped by different cultures. As a Vietnamese-born in Czechia we want to get to know more about our Vietnamese heritage and roots.

We believe it is important to learn and understand one’s culture. This solidarity project is about sharing stories and creating conversations to encourage open and honest discussions that confront the misrepresentations of Vietnamese culture. We aspire to build a safe space where people can prosper and feel secure in exploring and accepting their cultural identities without fear of judgment.

There is a desire to enable and ensure an inclusion in the society. By sharing historical background and life stories, Czech people would have insights into Vietnamese immigrant’s life.

Roots of the Future is about breaking a new ground and creating a welcoming space for exchange and learning.

Here we will share our journey.

-

To the Future and Beyond!

Let us take you on a journey to teach you about the history of our parents and close ones, who moved to foreign countries in hopes of finding a better life.

This blog was created for those who are interested in learning about family, cultural and mostly Vietnamese origins. Here you will get a chance to read stories of people who left their home back in Vietnam and came to Czechia and much more about Vietnamese heritage.

This project deals with the lack of information that some of young people have regarding their parent’s immigrant background. By sharing stories about our culture, we hope to connect more people together and underline the importance of knowing the history of (y)our culture. With this project we aspire to pass these stories on future generations.

By learning and understanding the history of our roots, we believe it is fundamental for shaping our future world.

„Don’t forget that the culture that is going to survive in the future is the culture that you can carry around in your head.“ – Nam June Paik

-

What happened at our last November event „Spojeni Sametem“ panel discussion

Little did we know

They say if you fail to plan, you are planning to fail. That’s why we started preparations a month and half beforehand for our event “Spojeni Sametem: Vietnamské a české vzpomínky na Sametovou revoluci” (United by Velvet: Vietnamese and Czech Memories of the Velvet Revolution)! While we were still enjoying the summer rays and sipping on cold fresh drinks little did we know that time to plan for our grand event was upon us.

Actually we started to make some plans at the end of August but when we got an offer to organize another intercultural workshop at Charles university our planning got delayed for a bit. The point is we didn’t have much time to waste. Excited to plan another event soon escalated to being concerned how we are going to manage to persuade Vietnamese potential candidates for our panel discussion to come and speak in front of the people. Little did we know more issues on that day would surface.

Finding a venue: checked

In September we got an offer from Charles university to organize an event for their 10th anniversary of Klub Alumni (a club for graduates from CUNI). Great! We thought. Let’s make our panel discussion during this program of Klub Alumni. Our worries about finding a venue for this event will fade away and we can shift our focus to other things like… conducting interviews with candidates for this topic – Velvet revolution.

Last time we talked about the Velvet revolution we met up with a formal Vietnamese student in Czechoslovakia. This time we reached out to him again and thanks to him we got in contact with another person from the Vietnamese community. Funny thing is, while we were manifesting and praying on our knees this meeting will be more successful, Mai bumped into him in Sapa and immediately started a conversation with him. He remembered our little project “Roots” and our event last year on the 17th November that he himself and his son attended. We told him about this event in November that we are planning and he agreed to meet us at the headquarters of his company.

One of the things we might be guilty of is keeping our hopes high. Because it would always come crashing down soon after that. Martin (our formal team member) told us to not make a big deal out of it. If you approach someone with a goal to meet up with them and talk about a certain topic they would often reject you because they believe they have nothing to say and they’re not that interesting. But we were always determined to at least meet up and I have to admit that we had a fun conversation every single time.

Getting back to our roots – topic I.

In the 80’s a lot of Vietnamese students and workers immigrated to Czechoslovakia during the communist regime. Some had a hard time integrating into the society and some did not. Some Vietnamese people engaged in activities and advocated for human rights. Others weren’t taking the risk of being deported and lived rather a simple life. This was our way to get back to our roots again. How did Vietnamese immigrants deal with the events in 1989?

My mom came to Czechoslovakia in September 1989. She told me everything she knew about the Velvet revolution was from watching the TV where she saw people protesting in the streets. But for my parents, one of the hardest things immigrating here was the language barrier. If you needed to make some papers done you had to do it through someone that could translate for you. It was quite a struggle for them because they didn’t know if they’d done it right or wrong. My mum remembers how shortly after the events in 1989 there were people called “skinheads” going around and attacking Vietnamese people in the streets and even in dormitories where Vietnamese people were living at the time.

How relevant this event was for us – topic II.

Hundreds and thousands of Vietnamese people were immigrating to Czechoslovakia especially in the 80’s and 90’s due to official bilateral relationships between these two countries. These contracts specified that they would work or study here for some time and after that they would return back home to Vietnam where they’d apply their new gained knowledge and experience. But a lot of them didn’t want to return back home. They knew that Vietnam wouldn’t be able to provide them with a lot of job opportunities and better future as Europe would do.

The Velvet revolution and change of regime played a crucial part in the lives of not only Czechs but also Vietnamese people. For them it meant that they could continue to work here. And the only way to do that was to start a business as entrepreneurs. Thanks to the Velvet revolution and former president Václav Havel, Vietnamese people were given a chance for a better future. But the story didn’t end here. A door with a new opportunity was opened for Vietnamese immigrants but the journey to new beginnings was far from a field of roses.

As children of immigrant parents we used this chance to explore and learn new things about our roots – our parents and the first generation of Vietnamese immigrants. We discussed this topic not only with our parents but in addition conducted a few interviews with the first generation of Vietnamese immigrants we have never met before.And just as our parents once struggled to learn and understand the Czech language when they first arrived, we now find ourselves in a similar situation, struggling to speak and understand Vietnamese.

Questioning future generations – topic III.

The Vietnamese minority is the third largest minority in Czechia but as time goes they’re starting to blend in with the majority more. The second and third generations of Vietnamese people have integrated into Czech society very well. They know the culture, they practice the traditions and they speak the language. I dare to say that most of them speak Czech more often than Vietnamese. Which is fine. But what’s gonna happen in 50 years?

Will future Vietnamese generations in Czechia still be able to remember their roots and speak Vietnamese? Probably yes, but I have my doubts seeing how the second generation is already struggling with their mother tongue.

But to end it on a positive note. Some of the young generations have now learnt to acknowledge and accept their Vietnamese identity. They are proud of their Vietnamese heritage and the major society has started to explore Vietnamese culture as well. Whether it’s through food, celebrating their holidays or attending Vietnamese festivals in Czechia. But at the same time it’s important to point out that not everyone accepts their Vietnamese heritage which is OK too.

The big day – the day everything went to hell

Even though the last event the year before was quite successful in numbers of participants, this year we were still worried not a lot of people would come. Despite having support from the university and the biggest festival for celebrating democracy and freedom in Czechia, promoting this event laid mainly in our hands. We were struggling a bit which topics we would want to cover during the panel discussion.

And then I got this idea to ask our followers on Instagram. But since nobody reached out to us I thought that it’s pointless anyway. And a funny thing happened when I looked into our feedback forms after the event. Someone wrote that next time it would be a great idea to try to ask people online which topics they’d be interested in being discussed!

The whole event of Klub Alumni lasted more than 4 hours from 6pm to 9:30 pm. A week before we placed an order with Vietnamese food from Sapa in Prague to ensure people wouldn’t starve and die of hunger. What and how much to order was a discussion in our team. We didn’t want to waste food but at the same time we didn’t know the exact number of people that would actually attend that day. We bought fried spring rolls, sesame balls and shrimp crackers that everyone enjoyed.

But surprisingly there was one person that complained there wasn’t enough food! :)) After all the break lasted only 15 minutes. So it wasn’t possible to have a bigger buffet.

Everyone in the team had their own role that they fulfilled for this event. Five days before that day we thought about how the panel discussion is mainly made of the older generation and so we thought it would be a good idea to age it down a little and put someone young among them. And that was Nikol, our team member, who kind of represented the voices of younger generations and our parents that came here working in manufactures. But things quickly went down south. They provided us with a venue and technical stuff. Our task was to ensure this panel discussion will go smoothly and care for the comfort of everyone.

We thought we planned every single detail and minute. But there were still some parts we didn’t consider. Technical difficulties. When they did the mic check everything was working perfectly. The acoustics of the room were good. But for some people that aren’t used to speaking with a microphone it was a little more difficult. Noises from the café below and the streets. That was something that made it harder for people to enjoy the discussion and something that was out of our control… kind of. The noise from the coffee machine. The noise from the tap water. The noise of people talking aloud in the café below. Everything was irritating as we were going up and down trying to deal with the issue.

“Hi, there’s an event going on upstairs. Can you please not talk that loud? Thank you.” “Hi, you have the tap water constantly running and it’s disturbing our event. Would you mind turning it off?” “Hi, people are almost struggling to breathe. Is it ok to open the door for a flow of air please?” Yeah well, that was apparently kind of a problem and we were hit with an answer

“I’ll have to ask the manager.”

When we first found out it was going to be in a Café I was startled but I thought since we are going to use microphones, people won’t probably see much in the back but at least they will hear the discussion. And boy was I wrong.

Our previous goal was to have a capacity of 80 people in the room. But soon after I saw the venue and found out how low the ceilings were, I suggested reducing the number to 60-65 people. In the end there were really about 60 people (cramped up) in the room which nobody expected. So I guess our goal was fulfilled after all!

If you had asked us if we enjoyed the event the answer would be “No.” The way things went wasn’t in our favour. The venue would be great for smaller gatherings but for this event I’d consider it a disaster. But at the end of the day we were grateful that they offered us a place to organize this event. Our expectations were placed just a bit higher. And some of people’s expectations were even a little higher than that.

Guilty of keeping our hopes to high

Here’s how we imagined and wanted the discussion to flow. First we reserved 10 minutes of time for introduction including talking about our initiative, providing people with a small historical context of this discussion and introducing our moderator with a small presentation. You know how people don’t arrive in time and there would still be people coming in at the start of the events? That’s one of the reasons we thought it would be a great idea to have a max 10 minutes intro and not start the discussion right away for late-comers. People knew about our speakers of the discussion and all of the focus would be of course shifted towards them. But they didn’t know much about our moderator (unless they really followed us on social media) so we reserved this introduction to also introduce him and sort of build up the tension and get people excited to the main part of the event. But I guess it kind of backfired? Since some people didn’t like how we took too much time wasting on some introductions on everything.

Moving on. The panel discussion started and so did the technical difficulties. We wanted to screen a short part of a documentary but unsuccessfully. The “stage” was cramped up. If we turnt on the projector screen it would project onto the speakers that were sitting there. The discussion… I don’t remember much from that but I know it was kind of going nowhere and it was already about 20-30 minutes into the discussion. We were standing beside and trying to sign to the moderator to speed things up a bit and later signing him to slowly start the Q&A discussion. That was stressful but funny at the same time.

Overall how can so many things go down south? If people were frustrated, we were a thousand more frustrated.

Leaving footprints on the sands of time

It was late and I wasn’t even in the mood to talk to people afterwards. But I’m always glad when they approach us and share their feelings with us. First thing I automatically ask them is how they enjoyed the event. And this time I was pretty curious. Surprisingly, some of them told us that they really enjoyed the event and nothing was bothering them even when we asked them again if they were sure.

Whether the event was a success or not at the end of the day we were glad to be given an opportunity to open up a discussion about this topic. Czech people perceive Vietnamese as a closed community and say they don’t know much about them. And so do we ironically. The Velvet revolution played an important role in the lives of Czech people and Vietnamese immigrants and we wanted to explore this chapter of our history and open a discussion together with other people.

Our aim is to support a conversation surrounding these topics, inspire others and motivate them to actively engage in these discussions.

We believe an open conversation and sharing different perspectives can bring a positive change to the world around us.

We want to encourage young people to confront big topics like these, explore their roots, heritage and the richness of their culture.

After all, we feel enormously grateful for the Faculty of Humanities Charles university for giving us space to get creative and Díky, že můžem for including us in this festival and celebration of democracy and freedom.

We’re thankful for those who came, helped us open this discussion and followed us this whole time on our little European Solidarity journey. ❤

Thank you and see you soon hopefully!

Team Roots of the Future.

-

Je libo chleba s koriandrem?

Mai Phuong Hoang

Představte si, že by Vietnamec a Čech měli společně vytvořit ideální tradiční snídani. Zatímco Čech by nejspíše sáhl po chlebu s máslem (a pravděpodobně i šunkou), jeho vietnamský kamarád by neváhal přidat koriandr, chilli nebo rybí omáčku. A právě v tu chvíli by se rozběhl malý interkulturní dialog. “Koriandr na chleba? To myslíš vážně?” říká si Čech v duchu. Vietnamec mu pohled oplácí s úsměvem, možná přemýšlejíc, proč by si někdo dával chleba bez výrazné chuti, jen s máslem.

Interkulturní dialog není žádná věda – stačí ochota se zaposlouchat a možná i ochutnat něco nového. Jde o to vystoupit z vlastní bubliny a přijmout, že různé kultury mají své „normálno“. Právě takové porozumění má hlubší význam než jen zkoušení cizích chutí; pomáhá rozvíjet respekt, bourat předsudky a přibližuje nás k jiným světům, aniž bychom museli opustit vlastní kuchyni. V praxi funguje interkulturní dialog všude kolem nás – v rodinách, školách, práci. Nejde jen o jídlo nebo jazyk, ale o přístup k odlišnostem. Neznamená to, že musíme měnit své zvyky; stačí se jen podívat na svět očima někoho jiného.

Interkulturní dialog je jedním z mnoha témat, kterým se zabývá i náš projekt Roots of the Future. Kdo čte HUMRa pravidelně, už ví, co jsme zač (článek o nás vyšel v čísle 3/24). Kdo o nás slyší poprvé, dovolte nám se krátce představit. Roots of the Future je solidární projekt, spolufinancovaný EU, který vznikl z iniciativy dvou studentů FHS – Martina a Vee – a jejich tří přátel, banánových dětí – Lindy, Mai a Filipa. Klademe si za cíl šířit povědomí o vietnamské kultuře a přibližovat životy vietnamské komunity v ČR. Skrze osobní příběhy a dialogy se snažíme překonávat kulturní rozdíly a inspirovat k vzájemnému porozumění. Zároveň hledáme sami sebe, svou identitu, své kořeny.

A teď zpátky k interkulturnímu dialogu, který byl hlavním bodem našeho posledního workshopu, uspořádaného 3. října 2024 v rámci festivalu Dozvuky FHSfestu – ECHOES. Jednalo se již o náš čtvrtý dialog, ale tentokrát skutečně interkulturní: kromě Čechů a Vietnamců se přidali účastníci z různých koutů světa, a abychom se všichni dorozuměli, probíhalo vše v angličtině (také poprvé).

Na úvod jsme prolomili ledy krátkým „icebreakingem“ s kartičkami Dixit, což nám pomohlo se lépe seznámit. Poté jsme se rozdělili do menších skupinek a sdíleli naše kulturní zvyky a hodnoty. Každý přispěl něčím zajímavým – od tradičních pokrmů až po hlubší kulturní specifika.

A reakce? Nechyběly překvapivé ani vtipné momenty. Jedna slečna z Číny hned odpověděla „communism“, když padla otázka na signifikantní hodnotu její kultury. Studentka z Indie nám přiblížila zvyky, které dodržují při svém nejvýznamnějším svátku Diwali, a které se vlastně moc neliší od těch vietnamských. Kolega z Indonésie nás zase rozesmál, když se svěřil, že tu díky pivu prožívá něco jako ráj na zemi, jelikož konzumace alkoholu je v jeho zemi tabu. Byla to směsice pohledů, které ukázaly, že každá kultura má své vlastní „normálno“, ale zároveň i mnoho společného.

Celková atmosféra byla velmi pohodová a všichni jsme si sedli, na konci došlo dokonce i k vyměňování kontaktů. (Já osobně jsem si připadala jako zpátky na Erasmu, bylo to perfektní.) Učebnu 2.41 jsme opouštěli s úsměvem na tváři, obohaceni o mnoho poznatků, byť trochu zklamáni, že čas utekl tak rychle. Fun fact k závěru: téměř všichni v místnosti byli překvapeni, jak moc dbají Češi na akademické tituly, a že si je dokonce uvádějí i na náhrobcích.

-

Jak si povídají kořeny s korunou

Autor: Mai Phuong Hoang

Zajímá vás, jaké je žít na pomezí dvou odlišných kultur a být každou nohou v jiné etnické identitě? Chtěli byste vědět, jak se prolínají a navzájem obohacují tradice a zvyky dvou různých světů? Nebo byste rádi jen nahlédli do života jedné z největších minorit Česka – do života Vietnamců? Pokud jste si odpověděli alespoň na jednu z otázek ano, tak by vás mohl zajímat náš projekt Roots of the Future.

Kdo jsme? Co děláme? A proč?

Roots of the Future je solidární projekt spolufinancovaný Evropskou unií, který vznikl z iniciativy 2 studentů Fakulty humanitních studií Univerzity Karlovy. Zrod projektu byl, dalo by se říct, tak trochu náhodný. Vše začalo, když se “Vee” Van Anh Tran vrátila po roce dobrovolnických aktivit v Itálii a hledala informace ohledně studia právě na FHS. Já bych řekla, že to byl osud, když se jí ze všech oslovených ozval jen jediný student, a to právě Martin Zelinka, který byl v té době studentem magisterského programu orální historie. Kromě toho, že jsou oba rodáci z Českých Budějovic, je spojoval zájem pro vietnamskou kulturu – Vee z hlediska poznávání svých kořenů a Martina, jak vietnamská kultura může obohatit českou a naopak. Společně tak s dalšími 3 členy, dětmi vietnamských imigrantů – Lindou, Mai a Filipem – položili základy projektu, který má za cíl šířit povědomí o vietnamské kultuře. Skrze vyprávění příběhů se snaží překonávat kulturní rozdíly a přiblížit životy vietnamských přistěhovalců. Tato témata projekt rozebírá na svých přednáškách, workshopech a sociálních sítích. Cílem Roots of the Future je spojovat lidi, kteří – stejně jako jeho členové – hledají svoje kořeny a žijí na pomezí různých kultur. Proč zrovna název Roots of the Future? Je to jednoduché. Abychom poznali korunu stromu, musíme nejprve pochopit jeho kořeny. Tím, že studujeme naše kořeny, tedy naše předky, lépe poznáváme sami sebe – generaci budoucnosti.

Kdo jsem já a proč vám o tom vlastně píšu?

Já jsem studentkou VŠE, čerstvě nový (neoficiální) člen projektu a stejně jako většina členů „Roots“ i já jsem takzvané banánové dítě – zvenku žlutá uvnitř bílá. Ano, možná to zní trochu hanlivě, ale tímto termínem se ztotožňuje značná část 2. generace Vietnamců v ČR. Vzhledem k tomu, že jsme se v Česku narodili a strávili zde většinu našeho života, je česká kultura, jazyk, zvyky a tradice v nás hluboko zakořeněná. Zato vietnamskou kulturu a jazyk mnozí z nás znají jen povrchově, jelikož naši rodiče byli příliš zaneprázdněni prací, aby nám mohli poskytnout život, který sami nikdy neměli. Zároveň se ocitli v zemi daleko od jejich vlastního kulturního zázemí. Vyrůstat ve dvou tak odlišných kulturách pro nás není taková legrace, jak se může na první pohled zdát. Není divu, že v jistém věku na mě dopadla krize identity. V podstatě mám 2 domovy, ale někdy mám pocit, že nepatřím ani do jednoho. Ve Vietnamu hned poznají, že nejsem zdejší, ve chvíli kdy otevřu pusu, v Česku zase není třeba ani pusu otevírat, protože můj asijský vzhled mluví za vše. Chvíli mi trvalo, než jsem si uvědomila, že si vlastně nemusím vybírat, že můžu patřit do obou světů, jak do toho českého, tak i do toho vietnamského. Abych se však mohla začít identifikovat jako Vietnamka, bylo zapotřebí lépe poznat svou vietnamskou část. Začala jsem od rodičů vyzvídat, jak se sem dostali a jaký byl jejich život ve Vietnamu, zajímala jsem se o naše zvyky a tradice, a dokonce jsem začala chodit na lekce vietnamštiny.

Roots of the Future zastřešuje vše, čím jsem si prošla a občas ještě procházím. Jsem nadšená z idei a poslání projektu, a hlavně z toho, že se mu všichni členové věnují ve svém volném čase s tak velkou dávkou entuziasmu a pokory. Roots of the Future není jen o poznávání své kultury a sebe sama, ale také o seznamování se s novými lidmi a jejich příběhy. Jak projekt, tak i jeho členové jsou otevření novým zkušenostem a výzvám a vítají spolupráce, které povedou k lepšímu světu pro další generace. Snažíme se vietnamskou kulturu přiblížit nejen nám, ale i okolnímu světu abychom zajistili budoucnost, kde se navzájem můžeme vnímat s tolerantností, trpělivostí a respektem nejen k naším kulturním odlišnostem, ale také tím co nás pojí. Vzhledem k tomu, že se s těmito hodnotami ztotožňuji, mohu říct, že jsem se přidala do správné party.

-

Pozvánka na akci „Spojeni Sametem“ – 14/11/24 od 19h

Datum a čas: 14. listopadu 2024 od 18:00 do 21:30

Adresa:ARCHA+, Na Poříčí 1047/26 110 00 Nové Město, Praha

👉Doplnění „příběhu dějin“ o další kapitoly, nad nimiž jsme se dosud nezamýšleli. Slovem i obrazem sdílené vzpomínky a prožitky vietnamských imigrantů a imigrantek v Č(S)R. Prostor pro budování mezikulturního porozumění i hledání významu svobody.

Registrujte se a pojďte si užít večer s pamětnickou diskusí, art talkem a promítáním!

⏰Akce má omezenou kapacitu, registrujte se prosím přes formulář: https://forms.gle/9VJWVvhh97Tnc613A

Vstupné je ZDARMA

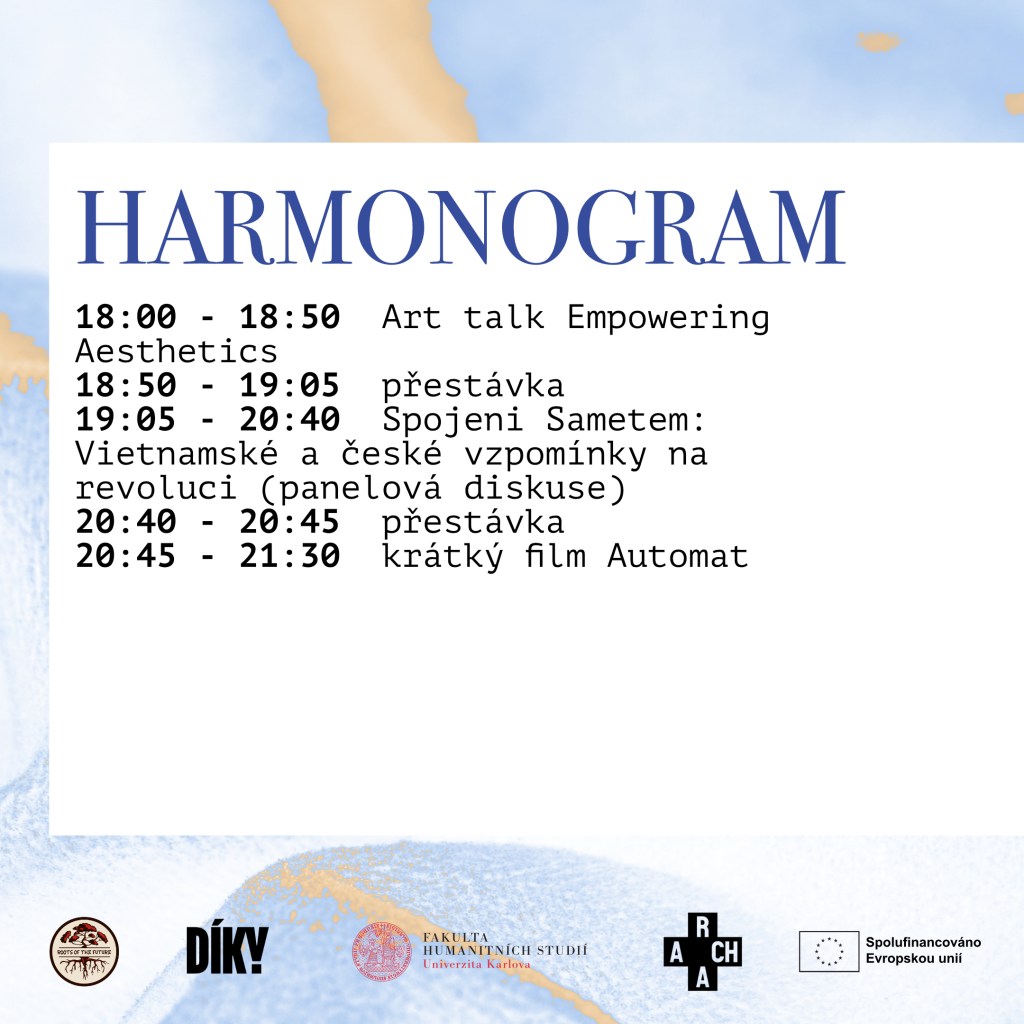

Harmonogram akce:

18:00 – 18:50 Art talk Empowering Aesthetics

- Paní doktorka Tomková představí kapitolu o umění vietnamské diaspory z knihy Empowering Aesthetics, která vyjde na jaře. Poté povede v kontextu kapitoly diskusi s umělkyněmi Kvet Nguyen a Quynh Trang Tran o jejich tvorbě a výstavě v 35m2.

18:50 – 19:05 Přestávka s občerstvením

19:05 – 20:40 Spojeni Sametem: Vietnamské a české vzpomínky na revoluci (Panelová diskuse)

- Dějiny etnických minoritních skupin českého národa se často opomíjí. Sdílením historie, která nás spojuje, chceme pochopit, že svoboda není černobílá. Chceme vytvořit prostor pro otevřenou debatu, budování porozumění a vytvoření více inkluzivní společnosti skrze dialogy a sdílení příběhů.

20:40 – 20:45 Přestávka s občerstvením

20:45 – 21:30 krátký film Automat

- Příběh dle skutečné události o vietnamské rodině ze Sokolova v roce 2012. Manžel Tung zůstává sám poté, co odlétá jeho žena s dítětem do Vietnamu. Otevírá nový bar a očekává příjezd hracího automatu s vidinou větších tržeb. Byl listopad a ten přináší ve vietnamské kultuře štěstí a hojnost. Avšak výherní stroj dává, ale i bere

Kontakty

Roots of the Future:– Instagram Roots of the Future

– Facebook Roots of the Future

– E-mail: roots.o.t.future@gmail.comPR oddělení FHS UK

– Instagram FHS UK

– Facebook FHS UK

– E-mail: pr@fhs.cuni.czOtázky? Napište nám!

👑 Akce se koná v rámci výročí 10 let Alumni UK Univerzita Karlova a Týdne svobody festivalu Díky, že můžem. Pořádá Fakulta humanitních studií Univerzity Karlovy ve spolupráci se Evropským solidárním projektem Roots of the Future, který je spolufinancován EU.

-

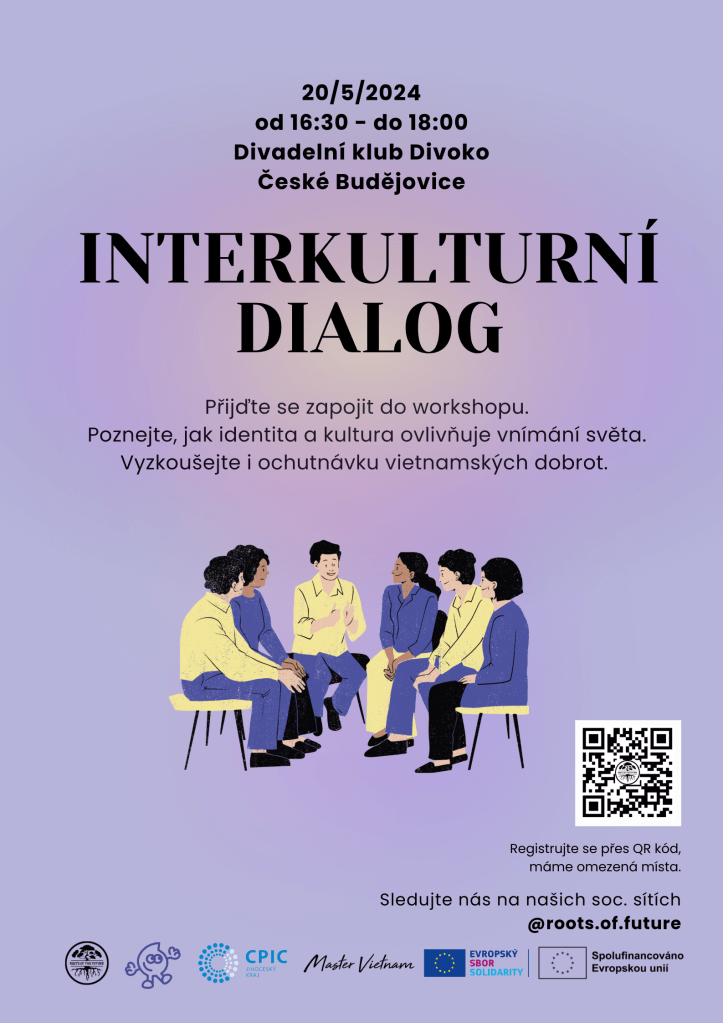

Pozvánka na Interkulturní dialog v Českých Budějovicích

Srdečně bychom Vás chtěli pozvat na jedinečnou akci, která se bude konat v pondělí 20/5 v rámci Budějovického Majálesu!

Zapojte se do interkulturního dialogu! 💭

Mnoho lidí má různé pohledy na svět a chceme spolu pochopit, jak tato diverzita názorů může obohacovat poznání. Každý člověk má své vlastní zkušenosti a pohledy na svět, a že tato rozmanitost může přispět k bohatšímu chápání reality.

Cílem akce je objevit odlišné pohledy na svět, bořit předsudky a budovat porozumění. Připravili jsme si pro Vás hravé a interaktivní aktivity, které zapojí všechny účastníky a vytvoří důvěrné a bezpečné prostředí pro sdílení zkušenosti a názorů. Bude se to konat v neformálním duchu, a nebude to podobné žádné obyčejné přednášky, na kterou jste zvyklý, zapojit se může úplně každý nehledě na zkušnosti a vědomosti. Stačí zvědavost! :))✨

Pochopení odlišných názorů nám umožňuje lépe reflektovat vlastní postoje a přesvědčení. Konfrontace s jinými pohledy nás může přimět k přehodnocení našich vlastních názorů a k rozvoji kritického myšlení, což je zásadní pro osobní růst a intelektuální pokrok.

Datum: 20. května 2024 (pondělí) Čas: od 16:30 – do 18:00 Místo: Divadelní klub Divoko – Dr. Stejskala 19, 370 01 České Budějovice 1

Místo: Divadelní klub Divoko – Dr. Stejskala 19, 370 01 České Budějovice 1❗MÁME OMEZENÁ MÍSTA, HONEM SI REZERVUJTE SVÉ MÍSTO❗

registrujte se přes odkaz ZDE

💸 DOBROVOLNÉ VSTUPNÉ

Součástí akce je drobné občerstvení a vietnamský čaj ZDARMA.Ve globalizovaném světě se stává čím dál tím běžnější, že lidé budou pracovat v mezikulturním prostředí. Kulturní rozdíly mohou být zdrojem nepochopení a nedorozumění, ale také zdrojem kreativity a inovací. Abychom předešli konfliktům a radikalizaci, představujeme workshop, který je cílený na uvědomění vzorců myšlení a vnímání světa. Skrze diskuze a interaktivní aktivity o identitě a kultuře budeme hledat porozumění mezi odlišné kultury. Propojíme kultury tak, abychom pochopili, že odlišnosti nemusí být jen příčiny ke konfliktům, nýbrž také bohatým zdrojem pro kreativitu, výměnu názorů a obohacení.

Naším cílem je zábavnou formou bořit předsudky a přinést nevšední kulturní zážitek skrze dialogy a interaktivní hry. Současně budete mít možnost ochutnat vietnamské dobroty 🥢a osvěžit se autentickým vietnamským čajem Master Vietnam. 🍵🇻🇳

🤔💭

Přidejte se k nám nebo pozvěty lidi, které by to mohli zajímat a buďte součástí interkulturního dialogu. Rozvoj tolerance k různým názorům a kulturám je důležitý pro mírové a produktivní soužití. 🤝

Workshop je navržený tak, aby umožnil lidem budování vzájemné důvěry a respektu, zároveň jsou zábavné a podněcují lidi k přemýšlení. Skrze interakce a debatu můžeme poznat nejen odlišnou kulturu, ale také nám pomůže k porozumění sebe sama a jak vnímání světa. Některé ustálené vzorce chování či myšlení jsme si schopni uvědomit pouze v momentě, kdy konfrontujeme odlišnost, a kdy si uvědomíme, že neexistuje jen jeden způsob chápání světa kolem nás.

Sledujte sociální sítě Roots of the Future a Budějovický Majáles. Pro případné změny Vás budeme informovat e-mailovou zprávou. Pokud máte jakékoliv dotazy, kontaktujte Roots of the Future

Email: roots.o.t.future@gmail.com

FB: https://www.facebook.com/roots.o.t.future

IG: https://www.instagram.com/roots.of.future/FB: https://www.facebook.com/budejovickymajales

IG: https://www.instagram.com/budejovickymajales/

Web: https://budejovickymajales.cz/o-festivalu

Tato akce je spolufnancována Evropskou Unií a realizuje se za podpory Jihočeského integračního centra a Master Vietnam.

About Us

The 12 month long project involves young people with immigrant background by encouraging them to be curious about their family history and cultural origins.

Roots of the Future is about discovering the Vietnamese roots of youngsters with immigrant background in the Czech Republic through storytelling and exchange.

We encourage youngsters to become curious about their own heritage and culture through sharing the stories of their parents and close people in order to identify multiple identities.

‘The youth is the hope of our future’.

– Jose Rizal

Follow Us On

Subscribe To My Newsletter

Subscribe for new travel stories and exclusive content.